This year James Cook University celebrates its proud legacy in historical research, writing and publishing through the Studies in North Queensland History Collection. In partnership with the JCU College of Arts, Society and Education (CASE), the Library has made available online, free digital versions of a selection of diverse works – both published books and unpublished theses all originating from the JCU History Department. To complement this showcase a series of blog posts provides a fresh response to each work through the contemporary lens of a prominent practicing historian. In today’s post, Associate Professor Richard White (University of Sydney) writes about No Swank Here?The Development of the Whitsundays as a Tourist Destination to the early 1970s by Todd Barr, published in 1990 by the JCU Department of History and Politics.

The history of tourism has been a Cinderella sub-discipline, at least until the foundation of The Journal of Tourism History in 2009. It is still often seen as a rather frivolous pursuit, something that might be done in a break, but not worthy of a serious academic analysis. As the journal’s first editor, John Walton, put it in the first issue, tourism history is often considered ‘too fluffy, frivolous, intangible and difficult to quantify’.1 That perspective ignores the fact that tourism is a huge world-wide industry, in Australia contributing more to GDP than agriculture and employing over double the mining industry’s workforce. And beyond its economic significance, it has profound social consequences for regions inundated by tourism, restructuring work patterns and social hierarchies. Its cultural impact affects ideas of place and race. It plays a role in environmental, gender, labour and even diplomatic history.

But perhaps the lack of recognition is not surprising when even those living in tourist regions don’t realise its significance. Only in 1973 did ‘tourism’ merit an index entry in the official Queensland Year Book. And Proserpine businessmen seemed particularly slow to recognise how tourism would transform their district.

|

| Tea towel: Whitsunday Islands: Glenn R. Cooke Souvenir Textiles Collection: item no. 19. Source: State Library of Queensland |

So when Todd Barr took on a history of tourism in the Whitsundays in 1990, he was a pioneer. His main concern was tracing the evolution of a tourism industry. Island tenants began supplementing farming income by providing facilities for passing steamship passengers and local holiday-makers. From the 1930s southern entrepreneurs began establishing resorts and offering cruises, but their activities remained relatively constrained until air services and port infrastructure made the Whitsundays more accessible by the 1960s.

|

| Lindeman Island luggage label, c. 1937, Source: State Library of Queensland |

While Barr’s focus is the economic development of the industry, he does not ignore some of its social and cultural implications. One of the most interesting tensions running through the book is suggested by its brilliant title, ‘No Swank Here’, taken from a slogan for the Happy Bay resort in 1938. It acknowledged that much of the attraction of an island holiday was its casualness. The primitivism of accommodation was part of the fun and an island holiday offered escape from the routines and formalities of ordinary life. Brampton Island’s resort owners used carrier pigeons to communicate with Mackay. The ‘illusion of seclusion’ enabled tourists to fantasise a beachcombing life.

|

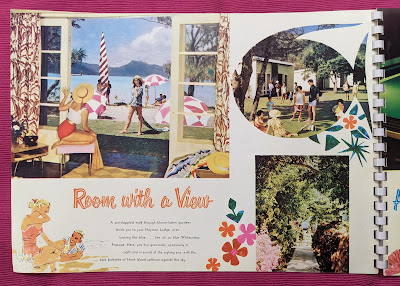

| Page from “Unforgettable Hayman”, c. 1950, 20 p., chiefly coloured, spiral binding. Source: North Queensland Collection, JCU Library Special Collections |

But the arrival of ‘swank’ was perhaps inevitable once southern entrepreneurs came to dominate: in Barr’s words the perfunctory activities of ‘quirky island settlers’ were turning into ‘a legitimate commercial enterprise’. And nowhere did ‘swank’ prevail more than on ‘Royal’ Hayman Island. Reg Ansett took over the lease and in 1950 opened a luxury resort aimed at an American or at least Americanised market. He promised a ‘sparkling Hollywood pool’, cocktail bar, live entertainment and rooms ‘furnished in exquisite taste’. Initially the dress code was rigorous: ‘slacks or shorts, with gaily coloured shirts are worn all day, but at night the ladies may be as glamorous as they please, and men are requested to wear dinner jackets or white tuxedos’. That strategy failed and Ansett had to halve his prices, complaining that even wealthy Australians ‘had been scared lest the “Continental touches” should require “socialite formality” when they wanted to relax’. Swank was alien to most Australian holidaymakers.

|

| Dining room at Lindeman Island, ca. 1945, Benussi family holiday post World War II. The oldest of all the resorts in the Whitsundays. Source: State Library of Queensland |

Nevertheless the new tourism industry brought a definite idea of what ‘southern’ and then ‘international’ tourists required. Some of the older operators bemoaned the arrival of package tours and increased wages, lamenting the days when they ‘could employ island boys at 15/- a week to do anything’. Barr has some understated fun with some of the newer, more elaborate promotional campaigns from the 1960s, extolling ‘gay resorts a-tinkle with ice cubes and laughter’. Publicity shifted from ‘castaway’ imagery to more of a South Sea fantasy, Hayman offering luau feasts and Lindeman employing Torres Strait Islanders ‘with flowers in their hair’ performing ‘sinuous native dances on the sand’. The industry congratulated itself on the success of the tour of duty through the southern states by the 1964 Coral Queen. The delightfully named Miss Ellie Sweetapple was, they said, ‘a very natural type of girl to whom all interviewers were attracted’. But the ‘ultra-civilised playground’ continued to sit side-by-side with simpler offerings, and Barr concludes that the very diversity of tourist experiences was crucial to the Whitsundays’ continued success, even if the ‘swank’ was curbed.

Barr ends with the hope that ‘When further research allows a general history of Australian tourism to be written, then the development of the Whitsundays as a tourist destination will have a secure place in the larger story’. Now those histories are being written, he can claim considerable credit for that hope being fulfilled.

1 John Walton, ‘Welcome to the Journal of Tourism History’, Journal of Tourism History, 1(1), p.1. https://doi.org/10.1080/17551820902739034

Comments